by Andy Xie / Morgan Stanley

Summary & Conclusions

India’s private asset value (stocks, properties, and gold) may have appreciated by about 100% of 2005 GDP since mid-2003, I estimate. The wealth effect of the extra paper wealth is the engine of demand growth. As long as asset prices remain high, India’s domestic demand will likely remain strong, I believe.

The government of India is determined to be supportive of the financial markets. Inflation and global liquidity are the two areas that could interrupt the current cycle. On the former, the government is in a position to change taxes to keep inflation within an acceptable range. Such an approach is likely to cause the current account deficit to widen further, which requires more capital inflow to sustain the growth dynamic.

India’s long-term fundamentals remain strong. Its flexible financial system is a major strength. The modernization of its consumer sector from retailing/distribution to production will be a major source of demand and productivity growth. The capital for funding this transformation requires India to boost its exports considerably. Its regulatory framework should also improve to accommodate the infrastructure development necessary for this transformation.

China and India

Four years ago, India’s Chamber of Commerce invited me to speak to the chamber about China in New Dehli. The fear that China would squeeze out India in trade was pervasive then. I visited India last week and found a different attitude there. While the apprehension of China is still there, the zero-sum-game view on India vs. China has dissipated. Both India and China have achieved high growth rates (9.9% for China and 8% for India in the past three years). This is the main reason that India has become more comfortable with China.

The development models of China and India’s are very different. China’s model follows that of other East Asian economies and pursues income expansion through maximizing trade and investment. Government policies aimed at incentivising export production and capital accumulation are at the heart of this model.

Furthermore, when China began opening up two decades ago, the government owned everything and there was no domestic business class to lobby against opening up or government exercising its power. This is why China has gone further than other East Asian economies in export/investment model.

India’s private sector leads its economic development. Under its democratic system, balance of interests and income distribution dominate the government’s policies. It has been leaning towards growth through liberalization of trade and domestic market in the past two decades also, though at a slower pace than China’s. In particular, its domestic business community has a powerful voice on how fast to open up domestic markets to foreign capital. Furthermore, its trade is much smaller than China’s and, hence, India is less vulnerable to international pressure in opening up its domestic markets.

India has an Anglo-Saxon style financial system, radically different from China’s government-controlled financial system. This has made India’s asset markets more sensitive to global liquidity cycle than China. This is the main reason that global liquidity, though supporting India’s asset markets, has become the engine of India’s growth now.

China’s supply response is much quicker than India’s. Because China’s business community is new and very focused on market shares, local governments are eager to create infrastructure, and the banking system is willing to support capital accumulation, China’s supply responds very fast to demand growth. This is why China’s exports have risen so fast in the current global boom.

India’s system does not allow the local or central government to respond to demand pressure easily; i.e., infrastructure buildup is gradual. Its business community is much more conscious of business cycles and does not build up capacity quickly in response to either low interest rate or demand growth.

These differences have led to a very different mix of demand growth in this cycle between the two economies. Production for export and construction drives China’s economy in the current cycle, while India’s consumption, funded by credit, is driving its demand.

I spoke on ‘India and China’ or ‘India or China’ in Delhi last week at the invitation of India Today. The former seems to have been the case for the past few years. Both have seen their economies and trade growing rapidly. India’s trade with China and Hong Kong grew by 43% in 2004 and 38% in the first 11 months of 2005, according to India’s Customs data. The rapid growth in India’s exports to China and imports from China suggests that the scope for cooperation between the two economies is greater than that for competition.

Convergence between the two is inevitable in the long run. China is reforming its financial system and exchange rate regime. The state banks are being listed. The stock market is opening up gradually to foreign capital. The exchange rate regime is very gradually increasing flexibility.

India’s political, business and media establishment has a strong consensus that India must build up its infrastructure to sustain high growth in the long run. Many politicians still hope that the current infrastructure can cope with growth for another two years. But, if growth stalls due to infrastructure insufficiency, the political system is likely to respond effectively. In the long run, India will become competitive in manufacturing and construction also.

Ten years from now, India and China may well compete in global trade of goods and services. But, this does not mean that it is bad for either. One Indian politician commented to me that competition between the countries was ok. It would keep both to strive harder, which is good for everyone in the end.

Wealth effect leads India’s demand growth for now

On the demand side, wealth effect appears to assume a large role in India. It is increasingly overwhelming the income effect in demand creation, I believe. On the supply side, imports have risen disproportionately. Of course, productivity and investment also play important roles in meeting the demand growth.

India’s current account balance deteriorated from $3.2 bn in surplus in 3Q03 to $7.7 bn in deficit in 3Q05. The swing is equal to 5.4% of 2005 GDP annualized. As India’s asset markets remain buoyant, there is no reason to believe that the trend would reverse.

It is possible that India could calculate the current account balance differently to reach a lower level of deficit. The customs data for trade deficit is much smaller than that in the BoP data. However, the calculation methodology would not change the magnitude of the swing in the past two years. India needs capital inflow to make an opposite swing in similar magnitude to reach balance and sustain demand growth.

The transmission from capital inflow into demand is very similar to that in Anglo-Saxon economies. India’s aggregate debt to GDP ratio has increased by 28 percentage points in the past five years, largely to fund household and government demand growth. India’s economic momentum, therefore, depends on capital inflow that sustains credit growth that sustains demand growth.

The financial story is the swing factor on the margin for India’s high growth rate. It does not negate the attraction of the underlying structural story. India is beginning to modernize its consumer sector, from retailing/distribution to production. India has about 60 shopping malls now with 300 planned. As the economies of scale in retailing increase, it would lead to the rise of a new distribution system with large businesses replacing traditional and multilayered small-scale distributors. As distribution scales up, it requires production to scale up also.

This modernization requires both investment funds to be available and sufficiently robust demand to make investment attractive. When this process began in China, it embarked on a massive export push to generate the necessary capital and income for demand. India is using its asset markets to make capital available and support demand at the same time. This strategy is workable as long as global liquidity is sufficiently strong. I suspect that India has to boost competitiveness by creating sufficient infrastructure, which would boost export income and add a source of income to support modernization.

Global liquidity and inflation could be headwinds

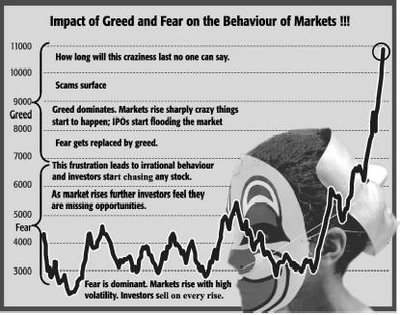

India’s stock market has become critical to its economic performance. The foreign inflow into its stock market is a major source of liquidity for funding its current account deficit, keeping interest rates low, and sustaining credit growth necessary for its demand growth. As the stock market is so important to the economy, the government is likely to take actions and provide rhetorical support to sustain the momentum in the market.

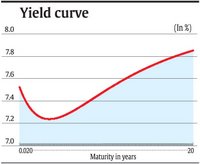

The overall background of global liquidity will likely decide the momentum of the Indian stock market and its economic momentum. The excess liquidity in India’s banking system has vanished in the past three months. The overnight interbank rate has jumped to 6.7% now from an average of 6% in December 2005, and the three-month interbank rate jumped to 7.5% from an average of 6% in December 2005.

The liquidity pressure is still intensifying. Some state banks have not raised either deposit or lending rates. They are resorting to borrowing in the interbank market to close their liquidity gap. They will have to raise deposit and lending rates soon.

In other economies that depend on asset markets, demand is quite sensitive to interest rates. But, India’s wealth on paper has increased so much and so fast that demand may not be sensitive to a small rise in interest rate. The tightening liquidity environment so far may not slow down India’s economy.

If global liquidity dries up, the Indian economy would slow down substantially. Global liquidity depends on the monetary policies in the G-3 and the risk appetite in the global financial system. The policy of the Bank of Japan is critical in that regard, especially since Japan’s retail flow into the Indian stock market is so important in the overall foreign inflow.

The Bank of Japan has just ended quantitative easing. The market is pricing in a small increase in interest rates by the Bank of Japan before the year end. We don’t know that that would be sufficient to cool the global liquidity boom or Japan’s inflow into the Indian stock market. Commodity prices and India’s SENSEX are correlated in that regard. If liquidity does dry up, they are likely to cool together.

Accelerating inflation and the accompanying rate hikes by the RBI would be another way to end the liquidity boom in India, because it would trigger a stock market correction and outflow of foreign capital from the Indian stock market. The government is keenly aware of this risk and is cutting taxes to decrease the notional inflation rate. It is possible that the CPI basket could be re-weighted to decrease inflation also. I think that we are not likely to see a shocking number on inflation in the coming months.

The short-term outlook for India, hence, depends very much on global liquidity. Betting on India’s stock market is equivalent to betting on sustained global liquidity boom, I believe.

The restructuring was accompanied by economic recovery towards the early 2000, which had a positive impact on the asset utilisation factor. Consequently, with costs under control, the benefits of incremental sales accrued at the bottomline level. This is clearly reflected from the reduced gap between operating margins and net margins in the last ten years (see adjacent chart).

The restructuring was accompanied by economic recovery towards the early 2000, which had a positive impact on the asset utilisation factor. Consequently, with costs under control, the benefits of incremental sales accrued at the bottomline level. This is clearly reflected from the reduced gap between operating margins and net margins in the last ten years (see adjacent chart).